With Medicare Support, CGX / PGX Genetic Cancer Testing Goes Mainstream.

Medicare will now cover FDA-approved CGX / PGX gene sequencing tests to match patients with cancer treatments.

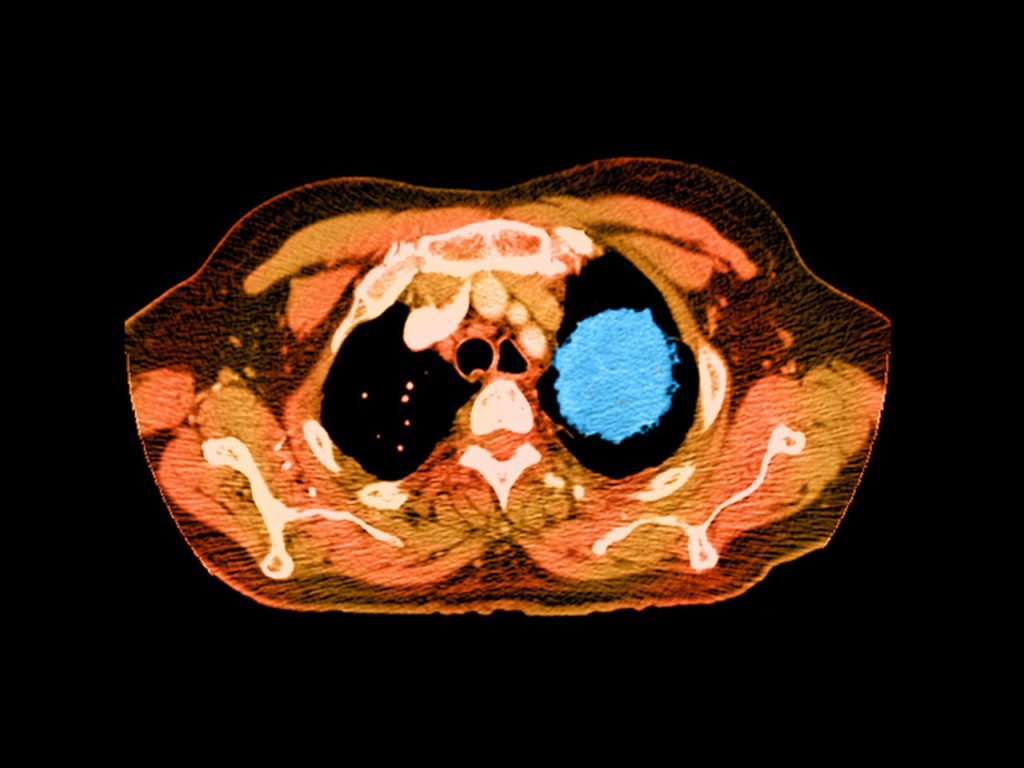

This year, nearly 1.7 million Americans will be diagnosed with cancer. Most will find out in the usual way; after having tiny blobs of tissue slurped up through a needle, smeared and stained on a slide, and put under the discerning eye of a pathologist. But starting this week, Medicare patients with advanced cancers will have access to a more 21st century diagnostic: Their cells can now be sequenced, matching patients with the drugs most likely to make a difference.

On Friday, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced that the federal healthcare program will cover the costs of cancer gene tests that have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration. Even if you’re not of retirement age, you should think this is a big deal. Private insurers take their marching orders from what Medicare does and doesn’t cover. Which means that genetic testing just became routine care for patients with advanced cancers. And that means precision medicine has finally broken into the mainstream.

“I think the big takeaway is that this type of robust genomic profiling has been viewed as an unmet need,” says Vince Miller, chief medical officer at Foundation Medicine, whose 324-gene panel test was approved by the FDA in November. It detects mutations across all solid tumor types associated with 15 already-approved targeted cancer drugs. It’s not the only test out there covered by the CMS decision, but it is the largest. Other commercial cancer panels include one from Thermo Fisher Scientific for lung cancers and one from Illumina for colorectal cancer. And any tests that gain FDA clearance in the future will automatically receive full coverage.

That means that in the short term, Foundation Medicine will almost surely see a massive boost in the number of formalin-fixed tumor tissues coming into its two laboratories. But it won’t have the monopoly many feared.

Olivier Elemento, director of the Caryl and Israel Englander Institute for Precision Medicine at Cornell, has been critical of the initial policy CMS proposed, which would have excluded genetic tests that are still under development—some of which doctors have been relying on for years. Elemento’s team at Cornell, for example, has developed a whole exome test that compares mutations in tumors against healthy cells across 22,000 genes. To date, it’s been used to help match more than 1,000 patients in New York state with the best available treatment options.

Under the final decision, doctors are still free to order non-FDA approved tests, but coverage isn’t guaranteed; each case will be evaluated by local Medicare administrative contractors. Which means Elemento’s test could still be covered. “To me this is a vote of confidence that next generation sequencing is useful for cancer patients,” says Elemento.

At least some cancer patients. So far, CMS is only covering these tests for stage three and stage four metastatic cancer sufferers. Most of them aren’t going to be cured. They might get a few more good months, maybe a year, tops. But for the population at large, tumor sequencing could have a much broader impact. Testing will generate huge volumes of genomic data on Medicare patients, whose treatments and outcomes can be easily tracked. All of that will help hospitals and companies gather evidence to validate their own tests, and help pharma companies fill their targeted treatment trials with genetically-matched patients.

Personalized medicine might be here, but it’s not yet personal.

Cancerous Genes

Getting the FDA’s first genetic cancer test approval took nearly two years and 220,000 pages of data. Here’s how Thermo Fisher Scientific led the way.

Targeting existing tumors for treatment isn’t the only thing you can do with mountains of genetic data. These companies are on the hunt to find signs of cancer in your blood, before symptoms appear.

Some people, like genomics pioneer Eric Schadt think all that data can go one step further. Like, say, curing cancer.